Curiosity

A collection of thoughts on, and examples of, curious thingsSeize the moment of excited curiosity on any subject to solve your doubts; for if you let it pass, the desire may never return, and you may remain in ignorance.

William Wirt

There are always those things that are never truly explained. We get the gist of what is going on, but we are never satisfied with these partial answers. Curiosity is that state of wanting to know more about something. The absence of curiosity is boredom, ennui, satiety, taking no interest, minding one’s own business, or uninquisitive.

Children are held up as the exemplars of curiosity and encouraging curiosity is one of the key strategies for ensuring the emotional and educational development of children. What happens to curiosity in adults? What makes some people more curious than others?

Psychologists are greatly interested in curiosity is a motivational force. Neurobiologists note that high levels of curiosity increase neurological pathways in the brain. The idea of curiosity was ‘rediscovered’ in the laboratories of the 1950’s when rats continued to explore mazes after their needs for water and food had been satisfied. What could explain this seemingly cause-less behaviour? Was there a biological drive that needed satisfying? A behavioural explanation is that curiosity is a response to complexity, surprise or novelty in the external environment. We use curiosity to order these stimuli and find a state of optimal stimulation: curiosity is used to remove the anxiety of too many new things in the external environment; whilst at the same time no stimulus results in a condition of boredom relieved by undertaking curiosity-seeking behaviour. In this model we do it because we respond to a need.

Yet there is something incomplete in what they say.

Cabinet of curiosities

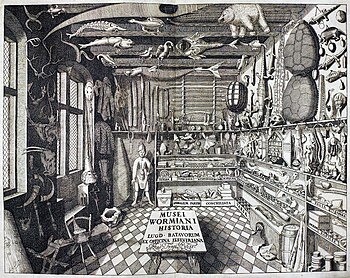

"Musei Wormiani Historia", the frontispiece from the Museum Wormianum depicting Ole Worm's cabinet of curiosities.

Cabinets of curiosities (also known as Kunstkabinett, Kunstkammer, Wunderkammer, Cabinets of Wonder, and wonder-rooms) were encyclopedic collections of objects whose categorical boundaries were, in Renaissance Europe, yet to be defined. Modern terminology would categorize the objects included as belonging to natural history (sometimes faked), geology, ethnography, archaeology, religious or historical relics, works of art (including cabinet paintings), and antiquities. "The Kunstkammer was regarded as a microcosm or theater of the world, and a memory theater. The Kunstkammer conveyed symbolically the patron's control of the world through its indoor, microscopic reproduction." Of Charles I of England's collection, Peter Thomas states succinctly, "The Kunstkabinett itself was a form of propaganda"Besides the most famous, best documented cabinets of rulers and aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science in Europe formed collections that were precursors to museums.

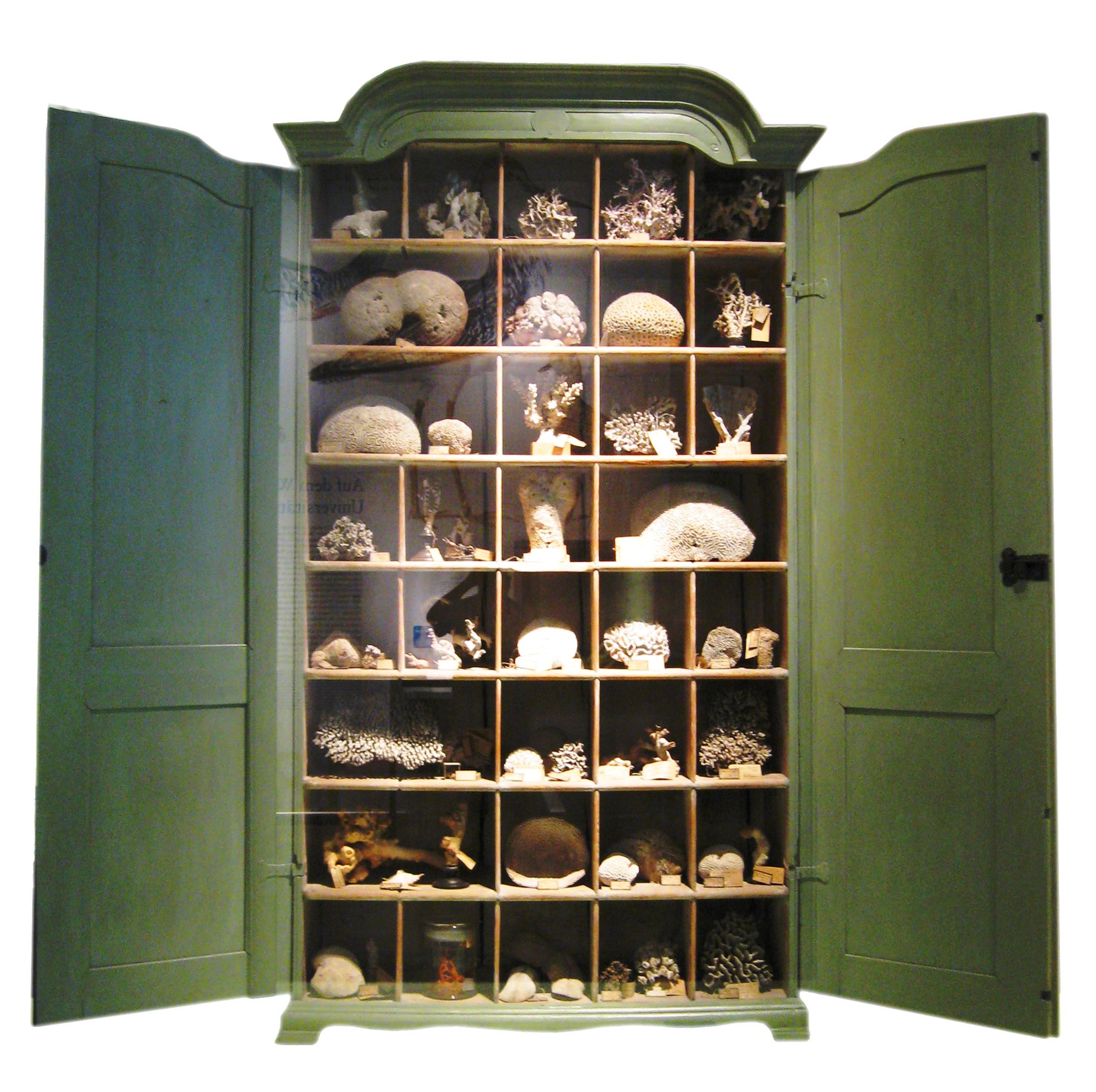

An early eighteenth-century German Schrank with a traditional display of corals (Naturkundenmuseum Berlin)

Deyrolle's Shell, Coral, Sponge, Starfish, and Sealife Collection. Paris, France.

https://www.pinterest.com/search/pins/?0=shelves%20with%20shells%20cabinet%20of%20curiosity%7Ctyped&q=shelves%20with%20shells%20cabinet%20of%20curiosity&rs=typed

Cabinets are often used by artists to present found or made objects and become integral to how the work is seen and its meaning (the cabinets are sometimes referred to as vitrines when used in this way) . This section of the resource looks at the history of curiosity cabinets – or wunderkammer (as they were originally called) – and also explores the reasons why Dion, and other artists in Tate’s collection, have chosen to use cabinets in their work.

What is a museum?

The museums of today have evolved out of two apparently basic aspects of human nature – our curiosity and our desire to collect. A building housing a collection of artefacts does not make a museum. A museum by today’s standards is formed from the sum of a building housing a collection, and the work of a staff in forming, preserving and interpreting that collection.

Where does the modern museum come from?

We know that earlier cultures such as the Babylonian (2200 BC – 538 BC), the Ancient Greek (1600 BC – 197 BC) and the Roman (396 BC – 410 AD) all had collections, which almost certainly had economic, religious, magical, historic, aesthetic or personal connotations for the owners. However, it wasn’t until the Renaissance (literally meaning rebirth) of art and literature in fourteenth-century that there consistently appeared collections which were preserved and interpreted – the modern definition of what a museum is.

These collections were created as a result of a growing desire among the peoples of Europe to place mankind accurately within the grand scheme of nature and the divine. This need developed during the fourteenth century and continued into the seventeenth century (the period of the Renaissance). These collections were generally known as cabinets, or curiosity cabinets, in England and France, and in the German speaking countries they were called kammer or kabinette. Greater precision was sometimes applied to the description of the collections in these cabinets, so there were kunstkammer (art cabinets), schatzkammer (treasure cabinets), rüstkammer (history cabinets), and finally wunderkammer (marvel or curiosity cabinets). Within the time period that these cabinets were created (the Renaissance) the terms wunderkammer or curiosity cabinet became the generic terms for them.

Wunderkammer or curiosity cabinets were collections of rare, valuable, historically important or unusual objects, which generally were compiled by a single person, normally a scholar or nobleman, for study and/or entertainment. The Renaissance wunderkammer, like the modern museum, were subject to preservation and interpretation. However, they differed from the modern museum in some fundamental aspects of purpose and meaning. Renaissance wunderkammer were private spaces, created and formed around a deeply held belief that all things were linked to one another through either visible or invisible similarities. People believed that by detecting those visible and invisible signs and by recognizing the similarities between objects, they would be brought to an understanding of how the world functioned, and what humanity’s place in it was.

The wunderkammer collections were displayed in multi-compartmented cabinets and vitrines, (which later in the Renaissance grew to be entire rooms), and were arranged so as to ‘inspire wonder and stimulate creative thought’ (Putnam p10). Exotic natural objects, art, treasures and diverse items of clothing or tools from distant lands and cultures were all sought for the wunderkammer. Particularly highly prized were unusual and rare items which crossed or blurred the lines between animal, vegetable and mineral. Examples of these were corals and fossils and above all else objects such as narwhal tusks which were thought to be the horns of unicorns and were considered to be magical.

As time passed and the wunderkammer evolved and grew in importance, the small private cabinets (which nearly all wunderkammer had begun as), were absorbed into larger ones. In turn these larger cabinets were bought by gentlemen, noblemen and finally royalty for their amusement and edification and merged into cabinets so large that they took over entire rooms. After a time, these noble and royal collections were institutionalized and turned into public museums. A very few examples of this process are: the cabinet of the London apothecary James Petiver (c.1663–1718) which was bought by Sir Hans Sloane, and became the basis of the British Museum. The great natural history cabinets of Fredric Ruysch (1638–1731) and Albert Seba (1665–1736), both of which were bought by Tsar Peter the Great of Russia (1672–1725), and can still be viewed in the kunstkammer gallery in St. Petersburg (Leningrad). And finally the Ark, the Wunderkammer of John Tradescant Senior (c.1570–1638), and John Tredescant the younger (1608–1662). This large and varied collection was open to the public for payment of sixpence (unlike the vast majority of other wunderkammer, which were kept private) in the Tradescant’s home in Lambeth. This collection had been recognized for it variety and even utility while controlled by the Tradescants, but it was under the ownership of Elias Ashmole (1617–1692) who inherited it by deed of gift through inheritance from John Tredescant the younger in 1659, that the collection’s scientific usefulness was finally and fully acknowledged.

Elias Ashmole donated the collection to Oxford University in 1677. He did this in the belief that the study of nature was ‘very necessaries to humaine life, health, and the conveniences thereof’ (MacGregor 1985 p206). The Ashmolean museum is the oldest public museum, and the first purpose built museum in the world. However, it was not its originality that brought recognition of its utility. A collection of curiosities had been a part of Oxford’s Bodlean Library almost from its start. What was almost certainly responsible for the Ashmolean Museum’s intellectual success was its laboratory and lecture hall, housed respectively on the ground and first floors of the original Ashmolean Museum building. These facilities helped enable scientific research and discovery, in much the same way that the research centers and library at the Tate galleries help art scholars and researchers today. The scholarly and educational aims that were Elias Ashmole’s founding objectives for the museum are still driving forces behind its work.The period from the late seventeenth to the early eighteenth century saw the decline and death of the Renaissance and the beginning of the classical age, the Age of Reason. During this period the beliefs of the Renaissance were challenged and overturned, and new ways of viewing and understanding the world were introduced. However, the Renaissance approach to collection and display did not die out completely at the end of the seventeenth century but continued in pockets, which survive in various forms even today. The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford is an excellent example of a modern curiosity cabinet with modern collection methods, meanings and purposes.

No comments:

Post a Comment